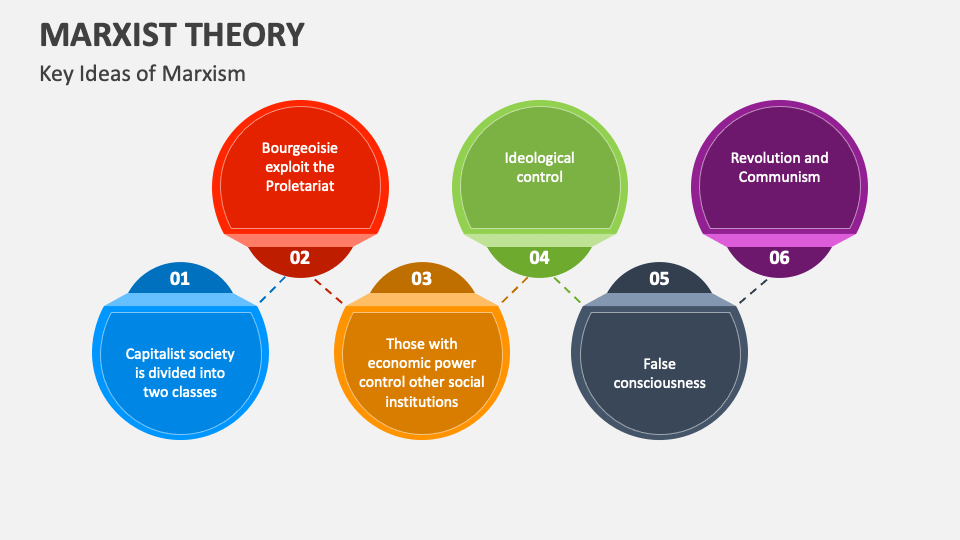

Marxist cultural analysis is a form of cultural analysis and anti-capitalist cultural critique, which assumes the theory of cultural hegemony and from this specifically targets those aspects of culture that are profit driven and mass-produced under capitalism.

The original theory behind this form of analysis is commonly associated with Georg Lukács, Antonio Gramsci, and the Frankfurt School, representing an important tendency within Western Marxism. Marxist cultural analysis has commonly considered the industrialization, mass-production, and mechanical reproduction of culture by the "culture industry" as having an overall negative effect on society, an effect which reifies the self-conception of the individual.

The tradition of Marxist cultural analysis has also been referred to as "cultural Marxism" and "Marxist cultural theory", in reference to Marxist ideas about culture. However, since the 1990s, the term "Cultural Marxism" has largely referred to the Cultural Marxism conspiracy theory, a conspiracy theory popular among the far right without any clear relationship to Marxist cultural analysis.

Definition

The term "Marxism" encompasses multiple "overlapping and antagonistic traditions" inspired by the work of Karl Marx, and it does not have any authoritative definition. The most influential texts for cultural studies are (arguably) the "Thesis on Feuerbach" and the 1859 Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Major Marxist figures in cultural studies include members of the Frankfurt School, the Italian revolutionary Antonio Gramsci, and the French structuralist Louis Althusser.

Marxism views cooperative social relationships as also sites of power and struggle. It examines even apparently non-economic human relations as structured by economic relations—even though "relatively autonomous". Cultural studies rejects the teleological dimension of some interpretations of Marx's thought (i.e., the inevitable overthrow of capitalism) to focus instead on matters of ideology and hegemony as they influence both politics and everyday life.

Frankfurt School

Critical theory, identified with the Institute for Social Research in interwar Germany and moving to the US after the rise of Hitler, applied Marxist as well as psychoanalytic concepts to the study of modern culture, in particular mass culture. The Frankfurt theorists, in particular Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, proposed that existing social theory was unable to explain the turbulent political factionalism and reactionary politics, such as Nazism, of 20th-century liberal capitalist societies. Also critical of Marxism–Leninism as a philosophically inflexible system of social organization, the School's critical-theory research sought alternative paths to social development.

What unites the disparate members of the School is a shared commitment to the project of human emancipation, theoretically pursued by an attempted synthesis of the Marxist tradition, psychoanalysis, and empirical sociological research.

Critical theory analyzes the true significance of the ruling understandings (the dominant ideology) generated in bourgeois society in order to show that the dominant ideology misrepresents how human relations occur in the real world and how capitalism justifies and legitimates the domination of people. According to Frankfurt School, the dominant ideology is a ruling-class narrative that provides an explanatory justification of the current power-structure of society. Nonetheless, the story told through the ruling understandings conceals as much as it reveals about society. The task of the Frankfurt School was sociological analysis and interpretation of the areas of social-relation that Marx did not discuss in the 19th century – especially the base and superstructure aspects of a capitalist society.

The essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", by Adorno's close associate Walter Benjamin is a key text of cultural theory. Benjamin is optimistic about the potential of commodified works of art to introduce radical political views to the proletariat. In contrast, Adorno and Horkheimer saw the rise of the culture industry as promoting homogeneity of thought and entrenching existing authorities. For instance, Adorno (a trained classical pianist) polemicized against popular music because it had become part of the culture industry of advanced capitalist society and the false consciousness that contributes to social domination. He argued that radical art and music may preserve the truth by capturing the reality of human suffering. Hence, "What radical music perceives is the untransfigured suffering of man.... The seismographic registration of traumatic shock becomes, at the same time, the technical structural law of music".

This view of modern art as producing truth only through the negation of traditional aesthetic form and traditional norms of beauty because they have become ideological is characteristic of Adorno and of the Frankfurt School generally. In particular, Adorno criticized jazz and popular music, viewing them as part of the culture industry that contributes to the present sustainability of capitalism by rendering it "aesthetically pleasing" and "agreeable". Martin Jay has called the attack on jazz the least successful aspect of Adorno's work in America.

Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Gramsci was an Italian Marxist philosopher, primarily writing in the lead up to and after the First World War. He attempted to break from the economic determinism of classical Marxism thought and so is considered a neo-Marxist.

Gramsci is best known for his theory of cultural hegemony, which describes how cultural institutions function to maintain the status of the ruling class. In Gramsci's view, hegemony is maintained by ideology; that is, without need for violence, economic force, or coercion. Hegemonic culture propagates its own values and norms so that they become the "common sense" values of all and maintain the status quo. Gramsci asserts that hegemonic power is used to maintain consent to the capitalist order rather than coercive power using force to maintain order and that this cultural hegemony is produced and reproduced by the dominant class through the institutions that form the superstructure.

Birmingham School

British Cultural Studies emerged in the 1960s and was housed at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies founded by Richard Hoggart (a non-Marxist socialist) in Birmingham and later directed by Stuart Hall (a Marxist). The Birmingham School developed later than the Frankfurt School and are seen as providing a parallel response. Accordingly, British Cultural Studies focuses on later issues such as Americanization, censorship, globalization and multiculturalism. As well as Hoggart's The Uses of Literacy (1957), Raymond Williams' Culture and Society (1958) and Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class (1964) by the Marxist humanist historian E. P. Thompson form the foundational texts for the school, with Hall's encoding/decoding model of communication and his writings on multiculture and race arriving later but carrying equal gravitas. Later key figures in the school included Paul Willis, Dick Hebdige, Angela McRobbie and Paul Gilroy.

The Birmingham School greatly valued and contributed to class consciousness within the structure of British society. Whereas the Frankfurt School extolled the values of high culture, the Birmingham School celebrated ordinary culture.

Marxism has been an important influence upon cultural studies. Those associated with CCCS initially engaged deeply with the structuralism of Louis Althusser, and later in the 1970s turned decisively toward Antonio Gramsci. To understand the changing political circumstances of class, politics, and culture in the United Kingdom, scholars at the Birmingham School made considerable use of Gramsci's concept of hegemony, which involves the formation of alliances between class factions, and struggles within the cultural realm of everyday common sense. Hegemony was always, for Gramsci, an interminable, unstable and contested process. Scott Lash writes:

In the work of Hall, Hebdige and McRobbie, popular culture came to the fore... What Gramsci gave to this was the importance of consent and culture. If the fundamental Marxists saw the power in terms of class-versus-class, then Gramsci gave to us a question of class alliance. The rise of cultural studies itself was based on the decline of the prominence of fundamental class-versus-class politics.

Another key concept developed by Hall and his colleagues, in their book, Policing the Crisis (1977), was Stanley Cohen's idea of moral panic, a way of exploring how the media of the dominant class creates folk devils in the popular imagination.

Cultural studies has also embraced the examination of race, gender, and other aspects of identity, as is illustrated, for example, by a number of key books published collectively under the name of CCCS in the late 1970s and early 1980s, including Women Take Issue: Aspects of Women's Subordination (1978), and The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain (1982).

Critique of identity politics and postmodernism

Contemporary Marxist philosophers have challenged postmodernism and identity politics, arguing that addressing material inequalities should remain at the center of left-wing political discourse. Jürgen Habermas, an academic philosopher associated with the Frankfurt School, and a member of its second generation, is a critic of the theories of postmodernism, having presented cases against their style and structure in his work "The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity", in which he outlays the importance of communicative rationality and action. He also makes the case that by being founded on and from within modernity, postmodernism has internal contradictions which make it unsustainable as an argument.

Frankfurt School Associate, Nancy Fraser, has made critiques of modern identity politics and feminism in her New Left Review article "Rethinking Recognition", as well as in her collection of essays "Fortunes of Feminism: From State-Managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis" (1985–2010).

"Cultural Marxism" conspiracy theory

While the term "cultural Marxism" has been used in a general sense, to discuss the application of Marxist ideas in the cultural field, the variant term "Cultural Marxism" generally refers to an antisemitic conspiracy theory. Parts of the conspiracy theory make reference to actual thinkers and ideas selected from the Western Marxist tradition, but they severely misrepresent the subject. Conspiracy theorists exaggerate the actual influence of Marxist intellectuals, for example, claiming that Marxist scholars aimed to infiltrate governments, perform mind-control over populations, and destroy Western civilization. Since there is no specific movement corresponding to the label, Joan Braune has argued it is not correct to use the term "Cultural Marxism" at all.

See also

References